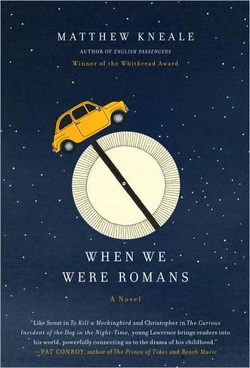

REview of When We Were Romans by Matthew Kneale

In When We Were Romans, Kneale commits wholly to a child's perspective—bad spelling, misused words and all—with fresh and moving results. Nine-year-old Lawrence joins his mother and younger sister on a spontaneous road-trip to Rome, holding fast to the hope that they can escape his mother's demons. Out of the mouths of babes: my hat is off to an author who successfully writes a novel from a child’s perspective, as it’s a woefully difficult thing to do. There are two main approaches, of course, and both can set the writer up for a world of trouble:

Some authors write from a child’s height. That is to say, they present the plot points from the view of someone who stands approximately four-feet tall, but—in order to include the details, nuances, and analysis the author wants and the story merits—that’s where the youth perspective ends. These books tend to disappoint me, because it’s hard to feel invested in a protagonist who lacks authenticity. Other authors commit to really and truly writing from a child’s point of view, complete with a child’s limited vocabulary, experience, and world knowledge. To say that staying true to this approach limits an author could be considered an understatement. Or it could be total bunk. It all really depends on your perspective. In When We Were Romans (Nan A. Talese, 2008), Matthew Kneale defies the odds, embraces this approach to the extreme, and delivers. Our narrator is Lawrence, a nine-year old British boy who accompanies his mother and younger sister Jemima on a whirlwind road trip to Rome, and the telling is so entirely his that it comes complete with bad spelling, god-awful punctuation, and thinking-pattern ticks such as assigning each person he meets a corresponding animal. (I like to think of myself as “tori cat”: a bit standoffish but quite affectionate to those who stick around long enough.) Lawrence’s trip is not without its perils, and his loving mother is not without her demons. When the family spontaneously abandons home and drives to Italy, they attempt the impossible: to outrun life’s challenges. At nine, Lawrence embraces this as an attainable goal. His trust in his mother is vast, and with her enthusiasm to buoy him, he believes in Rome as if it were Shangri-La. Simultaneously, though, he is a shrewd kid, sensing his mother’s oncoming meltdowns, manipulating her out of them as best he can, censoring realities he doesn’t think Jemima can handle, and working a room when needed. And, amazingly, everything he does feels 100% appropriate and true to a nine year old. Lawrence takes on these tasks with the same seriousness of purpose he applies to convincing his mother he needs a remote control car or fuming that Jemima gets to take more toys with her to Rome. To Lawrence, there is no difference: all of them have the same urgency, and he doesn’t yet have the skills to prioritize his efforts or control his emotions. This zeal leads to a bad end as the horrors they tried to outrun follow them to Rome, and Lawrence is left wondering—perfect nine-year-old musings—how he could be so betrayed. Kneale’s commitment to Lawrence’s voice and views is admirable. It’s a skilled writer who can create a compelling world through the eyes and mind of a child while still capturing the imaginations of readers of all ages. I’ll admit that my editorial inclinations made the beginning of When We Were Romans slow going, with moments of annoyance at Kneale’s idiosyncratic prose. That irritation gave way to amusement and delight, though, with such translations as le enfants (Lawrence’s mother’s pet name for her children) becoming “lesonfon.” If you can shake off your adult need for order and correctness, Kneale—and Lawrence—allow you to escape not only to another place and circumstance but to another age all together. Originally appeared in Fiction Writers Review a community of writers dedicated to reviewing, recommending, and discussing quality fiction from presses and writers with a focus on emerging authors. |